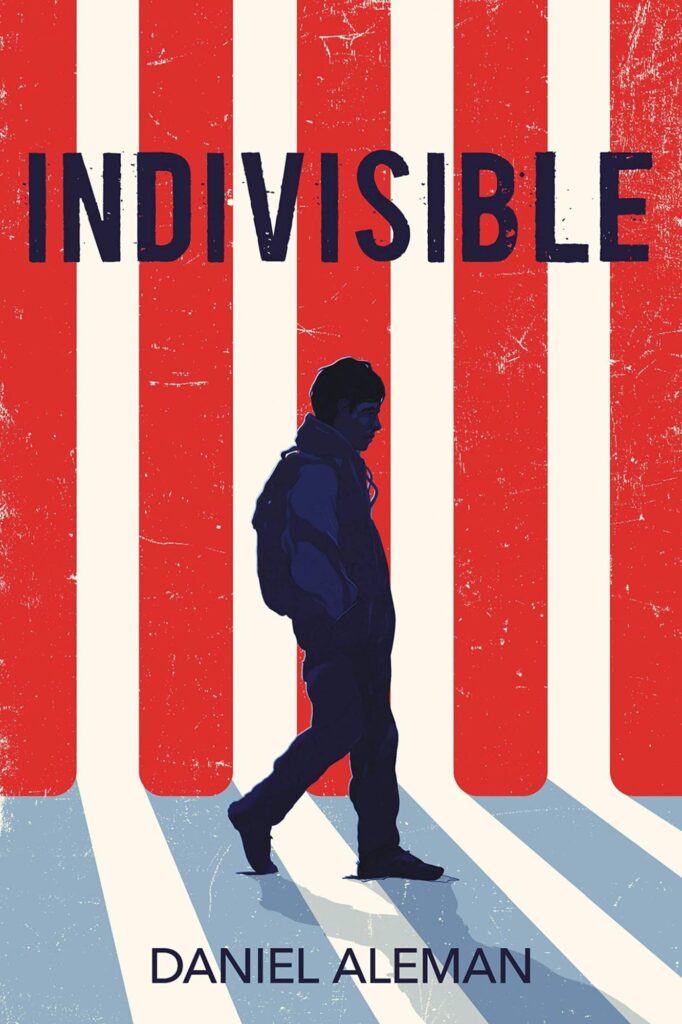

It feels like every year I get one perfect contemporary gay YA debut novel that just absolutely captures my heart. Last summer that was Adam Sass’ Surrender Your Sons, which I still rave about to whoever will listen to me. And in 2021, it is Daniel Aleman’s Indivisible. Before I start this review however, I must warn you that this is not an easy book. There is a lot of darkness there, and no easy answers.

16-year old Mateo Garcia is a New Yorker living the Manhattan working class life. He helps in his dad’s bodega. He has college aspirations and Broadway dreams. As well as the fervent hope that he will not, in fact, graduate high school having never kissed another boy. He is also the child of undocumented immigrants. Unlike him and his kid sister Sophie, his parents were born in Mexico, and crossed the border decades ago in search of a better life. And though they are both pillars of their community, not a day goes by without the underlying fear of ICE.

Then the worst happens, and Mateo’s life crumbles. Overnight, he finds himself having to become his sister’s guardian, learn to run his father’s bodega, and figure out what future he can have with his parents gone back to Mexico. And meanwhile, the feeling that he does not belong in any world drives him away from his closest friends.

Indivisible is not only a heart-rending story of hardship and perseverance, but also a meta-commentary on contemporary YA. The opening chapters show us all the trappings we know and love. An off-Broadway audition. A hurtful racial remark. A sensitive queer boy trying to find himself in a world that sometimes feels too large to comprehend. Then Daniel Aleman suddenly pulls the rug from under us, and gives us a story that is almost brutal in its earnest tragedy. And Mateo has to deal with truly adult issues before he has even had a chance to figure out being a teen.

At the beginning, I used the word “perfect”. Of course, no story is ever perfect, and Indivisible has its issues. I do wish that the pacing in the second half was a bit faster. While I fully understand the need for the catastrophic reality of Mateo’s life to have space to breathe, for me it did get to a point where I was ready for the book to move along. Another issue is the fairly contrived reason why he refuses to confide in his friends. While it does pay off emotionally in the end, I felt that in the actual moments when he could tell them, his reasoning wasn’t terribly convincing.

But the reason why I used the word “perfect”, is that Indivisible is greater than the sum of its parts. Any issues I might have with pacing or foreshadowing are irrelevant. Because the book was earnest, and powerful in a way that I have not experienced YA being in a very long time. Daniel Aleman comes out the gate swinging with this explosive debut, and I am thrilled to see what he does next.

P.S. As an aside, while reading I made a startling discovering. Aleman not only subverted the tropes of the typical contemporary queer YA. He also had a side character — Mateo’s gay friend Adam — actually have an entire traditional YA arc almost entirely off-screen. I truly hope that was intentional, because it made me smile during what was otherwise a very serious read.