This is something I’ve wanted to write about for well over a year, and I might be the only human in the world who is interested in the subject at this point. But as this is my blog, I get to go for it, and perhaps someone out there will care. Plus, it might give you an indication as to why my blog is named as it is.

I came out at 25. Late, by modern standards, and yet it felt like I had wasted half a life by then. I was never really technically “in the closet” to begin with. My mind is capable of phenomenal feats of compartmentalization, and so the “gay thing” had been stuffed so deep in my consciousness that I was in a permanent state of absolute repression. And so, I “came out” to the world about the same time I came out to myself. Moving to the United States, seeing life not as I had expected it would be, but as it could become, began a process of buildup in me that had only one possible healthy outcome.

The word just popped into my mind one day, unexpected and unasked for. GAY. It wasn’t any different from the million times I’d said or thought it before, and yet it was also profoundly, relentlessly new. Because it was about me. The moment was shocking, to be sure. I don’t think I did much else that night.

But it felt like a prelude, not the main event.

Two days later, I managed to type those three letters in a Skype chat with a friend back home. My fingers moving on the keyboard, the pinkie hovering over the Enter key. Then — almost despite myself — pressing down. It was the hardest physical feat I’ve ever accomplished. The sheer fever of the moment, the diamond-sharp awareness that your life is about to be split into a “before” and “after”. The condensed, immovable now of my first coming out to someone else was beyond the intensity of anything I have experienced, before or since.

The fever didn’t subside through the next few weeks of telling people face to face and embracing what it meant to me that they knew. That I knew. At first, the fear and underlying excitement would flare up every time — what if this is the one person who will reject me? Who will make a disgusted face, close up, turn around, curse at me?

It never happened. Despite the out-of-body aspect of it all, the self-defense mechanisms I had developed in the past two decades had picked the territory well. I was in a college town, surrounded by young, progressive people, many of them queer themselves. I was safe, or close enough. I was met with nothing but love and support.

Which is, of course, almost perversely disappointing in a way, when the climax of all those years of fear and trepidation is nothing nearly as dramatic as you had built up in your head. Because you being gay doesn’t matter to anyone else even remotely as much as it does to you…

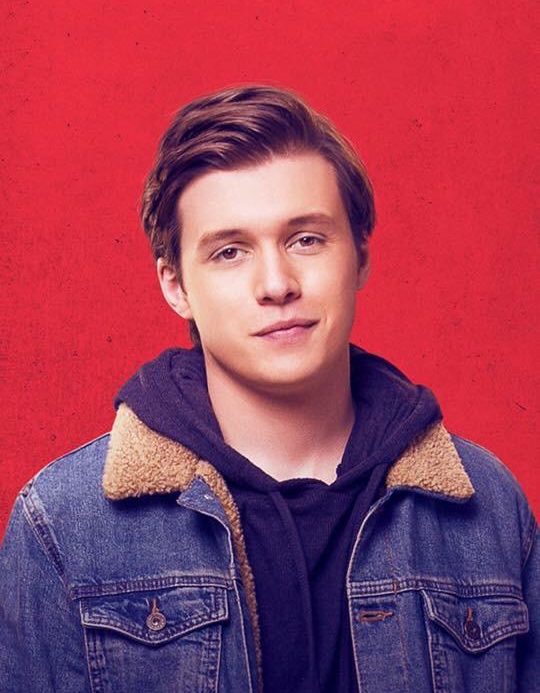

Love, Simon (directed by Greg Berlanti and based on Becky Albertalli’s breakout YA hit Simon vs. the Homo-Sapiens Agenda) was a quiet success. A mid-budget romantic comedy is already something of an outlier in this era of massive block-busters and indie sleeper hits. But the movie’s John Hughesque atmosphere and the disarming charm of its characters added to its status as the first teen movie by a major studio with a gay protagonist, to make it an event in a year marked by shattering cinematic experiences.

However, it was a much more personal revelation to me. Not because of any groundbreaking social message, or a profound, heretofore unseen approach to the queer experience. But because it captured the feelings I brought up earlier. The moment when you are not sure if your throat might close and refuse to form the word. The strange disappointment that your coming out isn’t nearly as shocking to the other person as you thought it would be. The overpowering emotion of being loved for who you are, not despite.

I saw this movie in theaters 9 times. I rewatch it every year on National Coming Out Day. It is not the greatest cinematic expression of our times, and even compared to some other contemporary queer movies, it may lack artistic and — to some — social depth. But that is a surface read. For all its gorgeous visuals and universal themes of desire and longing, Call Me By Your Name for example left me at a distance. There was little for me to resonate with. I rarely lounge for an entire summer in my family’s south Italian mansion. I have never had fiery romances with precocious hyper-intellectual teenagers. Peach is not my sex fruit of choice.

Which is not to diss what is truly an incredible movie. But Love, Simon did something else, and did it better. It showed a gay boy dealing with coming out in a relatable setting, and it showed the outpour of kindness and love that he received. It spoke with the language of personal experience, and it used small gestures, unspoken words, and that same fever that I myself lived through. And that message clearly worked, because the movie quadrupled its budget and survived heavy hitters like Ready Player One and Avengers: Infinity War in theaters.

We are trained by art to perceive suffering as the greatest form of storytelling. Doubly so for minority narratives. But just as with every other marginalized group, the queer experience is not always — not even predominantly — dramatic. It is not exclusively a tragedy to sympathize with. Sometimes it is just tender and simple, and full of small stakes that can matter more than anything else in the world. Sometimes it is just saying a word when silence feels like death.

And in this regard, Love, Simon was one of the most subversive and groundbreaking LGBTQ-themed movies of this past decade.

Be First to Comment